Saturday, February 28, 2009

Tarde-The Public and The Crowd

Tarde further argued that whereas individuals could simultaneously be part of several publics, they could participate in but one crowd at a time. Since crowds are comparatively limited in size, their influence may not extend beyond what participants and onlookers can see and hear. By comparison, publics are virtually unlimited in size and perhaps in the scope of their influence. But Tarde argued that the fundamental distinction between the crowd and the public was that interaction in the latter took the form of critical discussion. The result, Tarde suggested, is that publics yielded heterogeneity whereas crowds tended toward homogeneity.

Sunday, February 22, 2009

Forgotten Forefather of the Empirical Study of Public Opinion and Mass Communication

Tarde should be regarded as one of the forefathers of opnion and communication in general. He was all the more deserving for making diffusion so central to his thinking. The diffusion idea can be found in Tarde's better-known book-The Laws of Imitation. Furthermore, there was also a neglected essay-L'opinion et la foule, only parts of which have appeared in English.

The word "imitation" implies the influencee knows he is copying the influential, but the influential may not be aware of his role. If Tarde used the generic word "influence" instead of "imitation", he would be much better remembered. The interpersonal influence was overshadowed by the copycat aspect of imitation and by its proximity to the unthinkingness of suggestion and contagion. Maybe he chose "imitation" because he really believed that interconnected individuals copied each other in a semi-conscious way.

In his later work, as he moved from an interest in crowds to an interest in publics, he made it abundantly clear that conversation—not one-side copying—was the key to imitation, which was closer to the concept of influence. He also saw conversation as a major element in the formation of uniformities of opinion and behavior.

Monday, February 16, 2009

Invention, Imitation, and Opposition in Tarde's thought

According to Tarde, the three basic were interrelated, they were invention, imitation, and opposition. Tarde saw "invention" as the ultimate source of all human innovation and progress. The expansion of a given sector of society - economy, science, literature - is a function of the number and quality of creative ideas developed in that sector. Invention finds its source in creative associations in the minds of gifted individuals. Tarde stressed, however, the social factors leading to invention. A necessary rigidity of class lines insulates an elite from the populace; greater communication among creative individuals leads to mutual stimulation; cultural values, such as the adventurousness of the Spanish explorers in the Golden Age, could bring about discovery.

Many inventions, however, are not immediately accepted, hence the need to analyze the process of "imitation" through which certain creative ideas are diffused throughout a society. Tarde codified his ideas in what he called the laws of imitation. For example, the inventions most easily imitated are similar to those already institutionalized, and imitation tends to descend from social superior to social inferior.

The third process, "opposition" takes place when conflicting inventions encounter one another. These oppositions may be associated with social groups - nations, states, regions, social classes - or they may remain largely inside the minds of individuals. Such oppositions can generate invention in a creative mind, beginning again the threefold processes.

Monday, February 9, 2009

Rediscovering Gabriel Tarde

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~ ~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~ ~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~ ~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~ ~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~ ~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~ ~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

Tuesday, February 3, 2009

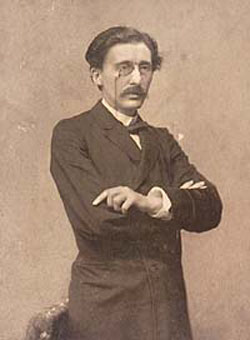

Gabriel Tarde-Biography

AKA Jean-Gabriel de Tarde

AKA Jean-Gabriel de TardeOccupation: Sociologist

Executive summary: Group mind, Theory of Imitation

1843

Gabriel Tarde was born in the small town of Sarlat, about one hundred miles east of Bordeaux. His father’s family own aristocratic particle.

He attened a school operated by Jesuit priests, who offered a rigorous classical training built largely on Latin, Greek, history, and mathematics. While always the first student in his classes, the sensitive young Tarde was pained by the Jesuit discipline, so much so that during his last three years, while a boarder at the school, he once even scaled the wall to escape temporarily. Although Tarde never failed to praise the classical training for binding together the leaders of nation with a common set of values, he retained a permanent distaste for socially imposed discipline whenever it limited individual freedom. The scholastic training also moved him toward a strong emphasis on the role of the intellect as well as an even more hierarchical conception of society than was held by many of his contemporaries.

1860

He left school. He first tried his hand at verse and dramatic pieces and then forsook. He was also fascinated by mathematics and considered attending the Ecole Polytechnique. The applied, ordered training, combined with its regimented social life in Ecole made him shun.

From 1862 to 1868

Tarde suffered from an eye disease which severely limited his reading. Together with the above-mentioned reasons, thus, he settled on the less demanding study of law.

From 1869 to 1894

He held a series of regional court posts in and around Sarlat because his many free hours could be spent at independent study and writing. Tarde developed the habit of walking the banks of the nearby Dordogne river, meditating about the works which he had read and elaborating his own thoughts. By the time of his thirty, he had drafted a series of notes to himself containing the essentials of his “law of imitation” as well as the outlines of the conceptual framework elaborated in his many later works.

1877

He married Mlle Marthe Bardy-Delisle, daughter of a magistrate.

1890

He published his most famous sociological work, The law of imitation.

1893

He became codirector of the Archives d’Anthropologie Criminelle journal, until his death in 1904.

1894

He was named director of criminal statistics at the Ministry of Justice in Paris.

1896

He applied his sociological perspective to political matters.

1898

He published Les lois sociales.

1899

He published Les transformations du pouvoir.

1902-1904

He was in a debate with Durkheim.

1904

He planned to undertake a series of empirical social psychological studies on school children with Alfred Binet, but the eye disease of his youth returned once again. He died in this year.

Social Power

In Capital, Marx explained social power in a materialistic way. Human labor can impart ‘vital energy’ to nature in creating use-values. Marx said ‘each individual holds social power in his pocket in the form of a thing’ (Marx, 1963, p. 986ff). The specific social character of each producer’s labor can only show itself when producers conduct the act of exchange. And money, a thing acquires social properties and social power. Marx describes this "transcendental" quality of a thing as fetishism. Such fetishism is not merely a delusion, or a sort of "false consciousness." In bourgeois society, money actually does possess the greatest power. However, it only possesses such power due to a specific social relationship which underlies it: atomized commodity owners who can constitute their social relationship to one another only by means of a thing, money. Money only has power because all social actors relate to money as money, that is, as an independent embodiment of Value. But insofar as individuals act as commodity owners exchanging products, they have no other choice but to stand in such a relationship to money. Having said that, fetishism does contain a delusional aspect in that money seems to possess an inherent social power. The fact that this power is the result of an automatically executed social process evades the grasp of everyday cognition. The process vanishes in its own result.